Loading page header ... or Your browser does not support JavaScript

My own boat - the "Tamara" |

|

Principal dimensions: L.O.D. 12.20 m (40' 0") L.O.A. 12.98 m (42' 72") L.W.L. 9.52 m (30' 11.5") Beam 3.40 m (11' 1.85") Draft 1.90 m ( 6' 2.8") |

Sail area: Main: 43.00 m2 (462 sqft) Staysail: 19.00 m2 (204 sqft) Jib: 23.50 m2 (253 sqft) Displacement: 10 700 kg (20 900 lb) (medium cruising trim) |

| Index of Topics: | |

|

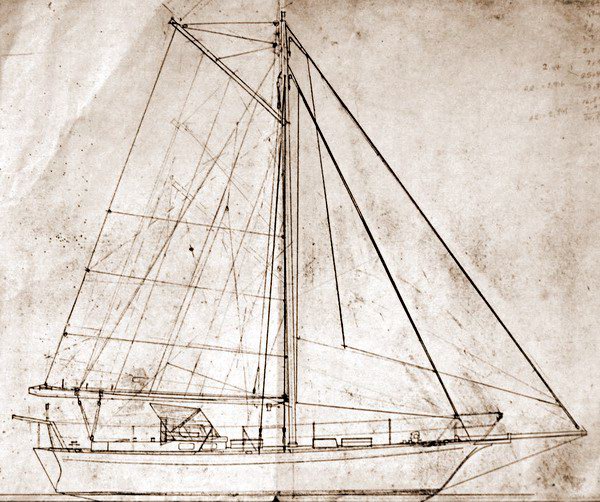

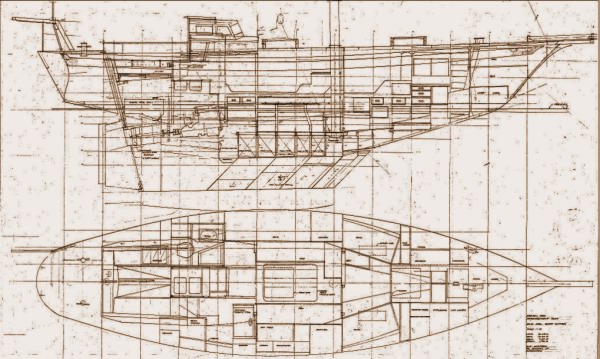

Accommodation plan and Profile: |

|

|

|

|

Design notes: "Tamara" is a round-bilged steel boat, gaff-rigged. I designed her in the early seventies for long-distance cruising. This was before PC's and CAD, so this design was done on the drawing board using splines, lead ducks and planimeter. The lines plan was drawn on Mylar film and the joinery drawings on drafting paper. I had been dreaming about building and sailing my own boat since boyhood and had been happily 'designing' my dreamboat for ages. Over time one gathers a lot of information and ideas and forms opinions. However, designing a cruising yacht, like any other design is about compromise. Some choices like safety, strength will top the list. Some features will fall to the pruning-knife of economy. Back to index Type of Hull : "Tamara" is of the traditional wineglass shape with longish overhangs and a slight clipper bow. She has moderate beam combined with, by today's standards, a fairly long keel with integral rudder. Back to index |

|

|

Hull construction materials: I investigated cold-molded timber construction, fibreglass reinforced polyester and metal. Cold-molded timber and fibreglass are a good choice for the building of round-bilged hulls - on the other hand they would require a shed to ensure correct conditions for glues and resins. Long term strength of glue joints was a worry and polyester work on a large scale did not appeal. Basically I felt uncertain about ultimate strength and both seemed to be demanding construction methods that were difficult to do successfully as a single hander. Next choice then was metal construction, aluminium and steel. Aluminium, although easily worked, even with woodworking tools, requires sophisticated welding equipment and a shed to avoid shielding gas being blown away. Steel construction is less demanding. Steel is relatively cheap as it is a major construction material and welding is easily done with a single phase arc welder. Furthermore, a building shed is not a necessity as manual arc welding is not affected by wind. Of course if it rains, one has to stop, but as soon as the steel has dried off one can carry on working. Steel as a boat building material has lots of pluses, not the least being its strength. No boat is invulnerable but steel boats get pretty close to the ideal. My conclusion then was that for serious cruising boat construction I would choose steel - in my opinion this is still the right choice today. Back to index Construction: Material: Low carbon steel. Plate thickness: Hull, cockpit and deck panels 3mm (1/8") turn of bilge 4mm (5/32") Keel fin 5mm (3/16") Keel base 12mm (1/2").Plate layout is important when building a round bilged hull. The easiest way to arrive at the optimum layout is to build a model and and use scale size "plates" cut from paper or thin card. Start off with the standard size (equivalent to 8'x4' or 2.44x1.22m), where this does not conform to the compound curves, halve the sheet size, make cut-outs, but don't use triangles or strips. The plate layout's point is to arrive at a layout that lets you use the largest plates and consequently the least welding possible. A wheeling machine would probably have been of great help in shaping the plates and if I had to build another round bilged boat I would invest the time to build one, which is not at all difficult. However, in the absence of this useful tool there are a few tricks one can use to achieve nearly as good a job. For the narrower plates at the turn of the bilge I had an engineering shop roll the plates to the radius that fit the frames and used shorter lengths to make allowance for the longitudinal curvature. This is basically the inverse to the radius chine method. The low coach roof is built from steel. To accommodate doors to the companion way and house the compass I built a small stainless steel superstructure with Lexan portholes on top of this cabin top. Back to index Sail rig: Bermudan, Gaff and Junk rigged vessels have cruised and circumnavigated successfully and mostly it is a matter of preferrence which rig one chooses. My rig of choice is the gaff rig. By its nature it is a simple rig to build for a homebuilder and easy on the pocket as spars and fittings are simple and the only rigging wire that needs to be stainless is the forestay(s). This is really the simplest and probably cheapest rig. The main can be easily raised and lowered - no fear of sliders binding etc. - the sail just slides down held to the mast by the lacing line. I gave the gaff main a much longer luff than the traditional proportions advise and omitted a topsail which only seems to add complications. This higher aspect ratio sail performs well on all points of sailing, but excels on reaching courses and before the wind. From personal experience I can confirm that it is a most successful rig for cruising and is easily handled at sea by one crew. The mast is strongest if stepped through the deck. On "Tamara" the steel tube mast is stayed via four shrouds and twin forestays. The jib is set flying and is run out to the end of the bowsprit on a ring. The shrouds have enough 'drift' so that no running backstays are required. Drift simply means the shrouds are angled aft of the mast. "Tamara" has a retractable bowsprit, as well as a short fixed stub bowsprit. The anchor chain runs over bowrollers at the end of the stub bowsprit - this avoids scratching topsides while launching and retrieving anchors. "Tamara" has twin running jibs which are set using "Twistle" poles. They consist of two hinged poles set flying. Unlike poles hinged from the mast this setup hardly interferes with the shrouds and for this reason can be trimmed through wider angles and allow efficient sailing with the wind on the quarter. If need be this rig can be used to self-steer by taking the sheets to the tiller. It takes a while to set the "Twistle" rig up, but that is fine in the trades, especially as it can be trimmed without gybing over quite a wide range of wind angles from port to starboard quarters. Sailing in the Indian Ocean we found that we were using the twin foresails less and less, instead we boomed out the staysail on the opposite side of the main. The main always had a preventer rigged. The boomed out staysail is inherently stable and won't back, so for more changeable weather conditions this is a versatile setup and can be easily and quickly gybed if the wind direction changes. Back to index Accommodation: "Tamara" was from the outset designed to only have fixed berths for three, i.e. our family, but she can actually sleep five if the saloon seats which are full bunk length are converted to berths. The galley is next to the companion to starboard, well ventilated. The heads arrangement with the forward facing WC is to port and the engine is between the two. On a slightly lower level is the saloon with a pilot berth to port and a chart table to starboard. Forward of that are two bunks separate from the saloon. The fore peak compartment has a workbench and lots of storage and lockers for sails and chain. She is a flush-decker with a low coach-roof and two large Lexan topped hatches as well as Dorade vents. The cockpit has deep coamings and a 150mm (6") drain outlet. Cockpit seats and sole are solid natural teak. Back to index Gear: Anchors: Two CQR's are permanently stowed on the short fixed part of the bowsprit and a large Danforth type is carried demounted near the pushpit. The main anchor is a 45lb CQR on 90m of chain. This is the anchor we actually used exclusively. The 35lb CQR with 20m chain and 5/8" line was only once deployed in the Caribbean while hurricane 'Andrew' formed to the north of us. That also saw the 45lb Danforth tested. The anchor winch is manual and did not see too much use as we have a chain pawl on the bow-roller. Once you sail with one of those you cannot imagine doing without as every link you haul in is grabbed and gained. Basically all up-anchoring was done manually by just hauling on the chain. Engine: "Tamara" has an old marinised Mercedes Benz diesel engine driving a variable pitch prop. The diesel tank of 250 liter (66 US gals) is situated under the cockpit. DC power generation: "Tamara" carries two 65W Solar panels, two wind-generators one of which can convert to accept a water turbine and thus produces power while sailing during the night. This is good for peace of mind when nav lights are on, or when the skies are overcast. Generator: A 3kVA petrol generator is carried on deck in a box and is capable of powering tools and the welder. There is no refrigeration except for a Coleman electronically cooled box. Back to index Self-steering: Naturally, to go cruising you really ought to have a reliable self-steering system. "Tamara" has an auxiliary rudder mounted on the transom, controlled by a horizontal axis vane. The system is based on the self-steering gear that was developed by Marcel Gianoli and used by Eric Tabarly on his Pen Duick . The cleverness of the hydro-dynamics described in detail in Bill Belcher's book on self-steering appealed to me and the practical experience confirmed that it is a superior gear. It has proven itself both reliable and sensitive, important features for ocean cruising. Back to index |

Loading first page footer ... or Your browser does not support JavaScript

Loading second page footer ... or Your browser does not support JavaScript